The Tar Format

Recently, I have been getting pretty interested in the tar format (along with its command on Linux). This article will be talking about that.

The format

The most common format that is similar to tar is zip files. Zip files serve two different purposes at once. First, it allows you to take multiple files, and combine them into one file. This is useful if you want to download a directory, or send some files in an email, or something of the sort. The second goal of a zip file is to compress data, so it is smaller, and can download faster. What makes tar interesting is that it only covers one of these goals, and is combined with other tools to serve both goals.

The tar format is very simple. It contains a header, and some information for every file, and then the contents. There’s not that much going on with this file format, which is part of why it’s so cool.

Compression

As I mentioned earlier, tar itself doesn’t do compression. That’s where other tools come in. The most common compression tool that you’ll see used with tar is gzip. GZip is a pretty old compression format, being over 30 years old. You can use it on UNIX systems by calling the GZip command on a file like this:

gzip foo.txt

If you then look at the folder with ls, you’ll see your foo.txt file is gone, replaced with foo.txt.gz. This is a compressed version of the file. We’ll get back to that in the next section.

A cool thing about this approach is that it means that tar won’t become obsolete. If someone comes up with a cool new compression method, tar will work out of the box with it. Zip, on the other hand, had to be updated to support Zstandard compression in 2020.

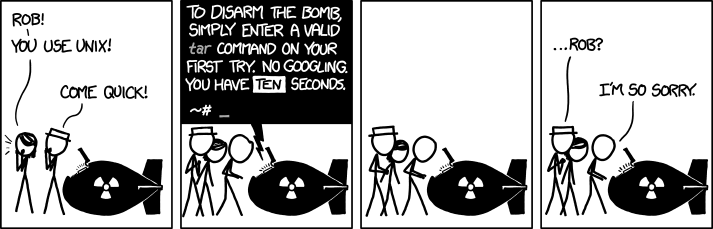

The Command Line Utility

The tar command has a reputation. It is usually viewed as being hard to use, and confusing. People resort to mnemonics to remember the combinations of flags that are needed to perform the operations that we care about. I feel like it would be easier to remember if we build up to those complex commands.

Let’s say we have a file called foo.tar in our current directory. We want to list the files contained within this file. To do this, use the -t flag on the tar command:

tar -t < foo.tar

If you don’t understand how the UNIX shell works, than this command will probably not make much sense. Programs on a UNIX shell have an input and an output, which are streams of text (or really any binary data). The tar command, by default, gets the archive from its input stream. The < foo.tar tells the shell to read from foo.tar and pipe that data into the tar command.

Once we understand that, we’ll try another command

tar -x < foo.tar

This will e(x)tract the tar archive, and put all of its files in the current directory. Again, it reads from standard input. But what if we want to create a tar archive? Let’s say we have the files 1.txt, 2.txt, and 3.txt. We can (c)reate an archive containing them like this:

tar -c 1.txt 2.txt 3.txt > numbers.tar

You’ll notice that we flipped the direction of the arrow. What this does is instead of routing the input from a file, we route the output to a file.

-v and -f

Usually, when you see commands involving tar online, you’ll see stuff like tar -xvf or tar -cvf. Why aren’t we using all of those letters?

First of all, I should point out that the order of those flags doesn’t matter. Usually, people put the main command first, but you can do whatever you want. the -f flag says that instead of reading and writing from the program’s input and output, you should do it from a file that you provide. So you can write

tar -xf foo.tar or tar -cf numbers.tar 1.txt 2.txt 3.txt to replicate those commands from earlier. This is useful mainly for reasons that I will bring up later.

The -v flag stands for verbose. What this means is that you output some text to standard error that tells you what’s going on. Standard error is pretty much the same as standard output, but it’s separate. This is good because otherwise, the information that’s being outputted would be added to the tar archive, and mess it up. In general, standard output is meant for code to read, and standard error is meant for humans (The name implies that the things that are sent to standard error are bad things. In my opinion, this is a bad name, and something like standard info would’ve been better). If you are creating or extracting an archive, it will output the names of all the files in the archive as it does it. This is good to make sure the command is doing what you want it to.

Adding compression to the mix

By default, tar can handle compressed files without you having to do anything special. But this is only true if you’re using the -f flag. Otherwise, the command has no way of knowing that you’re dealing with compressed information. But that’s no fun! This is how you can use tar with compression without all those silly flags:

tar -c 1.txt 2.txt 3.txt | gzip > numbers.tar.gz

The | takes the output from that first command, and pipe it to the input of the second command. We create an archive, compress it with gzip,and output it directly to that file. Now let’s go the other way:

gzip -d < foo.tar.gz | tar -t

This one uses gzip -d to decompress our archive, then pipes it to tar to list the files. Another cool thing that we can do is specify our compression level:

tar -c 1.txt 2.txt 3.txt | gzip -9 > numbers.tar.gz

We can put in any number from 0 to 9. Higher numbers will take longer to compress, but will be smaller.

Isn’t that so cool? All of those annoying flags can be replaced with a smaller amount of less annoying flags, and cool pipe symbols.

Conclusion

In conclusion, tape archives are cool and fun. Also, hopefully you can remember tar commands now.